Guide to African American Historic Sites

Learn More: Enslaved Africans living in Deerfield

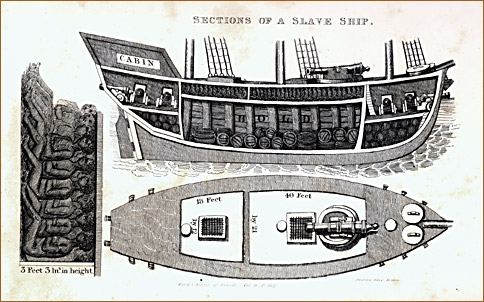

Caption: Sections of a Slave Ship, Robert Walsh, Notices of Brazil, Boston, 1831. PVMA Library

How did slaves arrive in towns like Deerfield?

In the early years of the slave trade to New England, most enslaved Africans were captured in Africa, and taken to the Caribbean before being sold and relocated to New England. As the number of enslaved Africans in New England grew between 1740 and 1775, slaves increasingly arrived directly from Africa, bringing immediate cultural and religious traditions with them.

Slave? Servant? Or Enslaved African?

Today, many historians use the term "enslaved African" to emphasize the understanding that "slaves" are human beings forced into a life of servitude. Historical documents, however, often refer "servants," which can describe both enslaved Africans and Native Americans, as well as white indentured servants. The historical term, "servant for life", was sometimes used instead of the word "slave."

What other forms of servitude were there?

Some laborers were bound through a contract to work for a master for a set period of time, at the end of which they would gain their freedom. Europeans called this arrangement "indentured servitude." Convicts, paupers, and those seeking to pay off their trip to America worked as indentured servants for terms of seven to ten years. Slavery was a very different kind of bound labor. Not only were slaves forced to work for life, but the children of an enslaved mother inherited her enslaved status.

Control and Resistance

To keep slaves from running away or rebelling, slave owners and civic leaders attempted to dictate most aspects of slaves' lives. Despite these controls, enslaved people managed to maintain their lives and culture. They resisted their condition in many ways, including quietly and sometimes secretly carrying on cultural traditions such as telling traditional stories or adhering to spiritual beliefs, socializing away from the oversight of their oppressors, or running away. Our knowledge of African American life and customs in the 17th and 18th centuries is often derived from white observers who may have been unfamiliar with or uninterested in the African heritage and the personal lives of the region's African-American population. There is much that we don't know about their successes or their struggles to overcome slavery.

Caption: Rev. Stephen Williams, c. 1750. Memorial Hall Museum

Slavery and the church

Many New England ministers, like other professionals and elite members of society, owned slaves. The diary of Reverend John Williams' son, the Reverend Stephen Williams of Longmeadow, MA, provides insight into one minister's thoughts about owning humans. In 1730, Williams writes "Oh Lord, help us to do our Duty- to all committed to our care," later noting his sermons speak to the duties of servants & masters. When one of his slaves died in 1751, Williams acknowledged the burden that bondage represented to slaves- "this day Stanford is laid in dark Silent Grave ye place where ye Servant is free [from] his master." Incredibly, even after his slaves Tom and Cato drowned themselves in 1756 and 1763, Stephen Williams remained uncertain if he should free his slave Peter out of concern that he not "do anything, that may be dishonourable" to his religion.

The writings of the Reverend Cotton Mather, an extremely influential Boston

minister and slave owner, offer insight into the Christian duties of 18th

century slave masters. The following excerpts are from The Negro Christianized,

written by Mather in 1706:

"O all you that have any NEGROES in your Houses; an Opportunity to

try, Whether you may not be the Happy Instruments, of Converting,

the Blackest Instances of Blindness and Baseness,

into admirable Candidates of Eternal Blessedness. Let

not this Opportunity be Lost; if you have any concern for Souls,

your Own or Others; but, make a Trial, Whether by your Means, the most

Brutish of Creatures upon Earth may not come to be disposed,

in some Degree, like the Angels of Heaven; and the Vassals

of Satan, become the Children of God…. It is come to pass

by the Providence of God, without which there comes nothing to

pass, that Poor NEGROES are cast under your Government and Protection…..

Who can tell but that this Poor Creature may belong to the Election of God! Who can tell, but that God may have sent this Poor Creature into my Hands, that so One of the Elect may by my means be Called; & by my Instruction be made Wise unto Salvation! The glorious God will put an unspeakable Glory upon me, if it may be so!"

By converting their slaves to Christianity, ministers, like many other

slave owners, hoped slaves would be inspired by such Christian sentiments

as subservience to the Lord, and that such Biblical interpretations and

church sacraments would help control slaves' behavior. Some owners promoted

literacy so that they would be able to read the Bible. Many slaves, however,

especially those who had been raised in Africa, resisted Christianity

or sustained their African beliefs in tandem with Christian tenets. Did

slaves accept Christianity willingly? Or was it one more demand placed

on them by their owners?

Divided Families

Nine-year-old Phillis was one of three slaves listed in the 1741 probate inventory of Nehemiah Bull, minister of Westfield, MA. In 1741, she was sold to Timothy Childs (site 7 on map) for $100.

"Know all men by these presents that we ... Executors to the Last Will & Testament of the Revd Nehemiah Bull Late of Westfield Deceased for & In Consideration of the Sum of One Hundred pounds Current Bills... Paid by Timothy Childs of Deerfield... have by these presents sold... a certain Negro Girl named Phillis of about nine years of age to have & to hold that Negro Girl ... During the term of her Natural Life..."

Bill of sale, 1741. Thomas Williams Papers. New York Historical Society

The sale of child slaves shocks us today, but in the 18th century, enslaved children were regularly sold and parted from their families. Many slave owners preferred to purchase children in the belief that younger slaves would learn English more easily, adapt more quickly and develop stronger loyalties to a master and his family. It is not hard to imagine the devastation of separation these children and their families experienced. Although slaves' ability to maintain ties with family members was sometimes difficult, they struggled to stay connected.

Daily labor

Slave labor in New England was as diverse as the economy. Enslaved Africans were often given training in specialized skills to work in trades. Others, such as Cato and Titus, slaves to Deerfield's minister, the Reverend Jonathan Ashley, performed manual labor, usually agricultural, as needed for Ashley and others. In the household, Cato's mother Jenny took care of the Ashley children, cooked the family's meals over the kitchen fireplace, washed and mended the clothes, cleaned the house, and worked in the kitchen garden.

Connections to Africa

Documents and archaeological discoveries elsewhere reveal that many slaves stayed connected to their African culture. Deerfield historian George Sheldon heard about the Reverend Jonathan Ashley's slave Jenny and wrote that she "fully expected, at death or before, to be transported back to Guinea; and all her long life she was gathering, as treasures to take back to her motherland, all kinds of odds and ends, colored rags, bits of finery, peculiarly shaped stones, shells, buttons, beads, anything she could string." Jenny's son, Cato, created a similar collection. George Sheldon remembered that for many years Deerfield residents referred to buttons as "Cato's money."

What could this mean? Jenny's and Cato's collecting likely reflected

their cultural and spiritual connection to Africa. Among the Bakongo peoples

of West Central Africa (where many people were captured into slavery),

people gathered objects like stones, roots, metal rings, and beads to

make Nkisi bundles, or medicines of the gods. These sacred bundles could

help direct the gods to provide aid for humans on earth.

Slave names

One way slave owners exerted their control over their slaves was to choose new names for them when they first arrived in the colonies or when babies were born to the enslaved, taking away an important cultural right to name members of one's own family. Names that were commonly chosen were sometimes derived from Greek or Roman history, the Bible, or classic literature (like Caesar, Mesheck and Titus), or place names such as Boston and Hartford. At other times, slave owners allowed enslaved people to retain their African names. Names such as "Phillis" and "Cuffee" reflect the African practice of naming children after days of the week. Many slaves maintained kinship by bestowing parent's or grandparent's names, of whatever origin, to a newborn, thus preserving these names into the 19th century.

How did slaves interact with each other?

Enslaved African Americans crossed paths in daily life on a regular basis. Joseph Barnard (site 15 on map), who owned Prince, was one of many Deerfield residents who rented out his own and hired neighbors' slaves, such as Titus from Daniel Arms (site 10). The seasonal demands of agriculture required many hands at various times of the year. Throughout the town, work, commerce, and daily life presented many opportunities for slaves to interact, communicate, and form relationships with one another. However, the personal side of slaves' experience often remains invisible.

Runaway Slave: Attempts to Resist

"Ran-away from his Master, Joseph Barnard of Deerfield a Negro Man named Prince, of middling Stature, his Complection not the darkest or lightest for a Negro, slow of Speech, but speaks a good English; He had with him when he went away, an old brown Coat, with Pewter Buttons, a double-breasted blue Coat with a Cape, and flat metal Buttons, a brown great Coat with red Cuffs and Cape, a new brown Jacket with Pewter Buttons, a Pair of new Leather Breeches, Castor Hats, several Pair of Stockings, a Pair of Pumps, A Gun and Violin. Whoever shall apprehend said Fellow and convey him to his master, shall have Ten Pounds old Tenor, and all necessary Charges paid by Joseph Barnard Deerfield, Sept. 18, 1749

All masters of Vessels and others are caution'd not to conceal or carry off the said Negro, as they would avoid the Penalty of the Law"

Boston Post Boy, 1749

Where did Prince go? Why did he have all those clothes? Did he hope

to earn money playing the violin? Most of our very few physical descriptions

of enslaved African Americans are found in advertisements for runaways.

Running away was not uncommon among slaves throughout the American colonies

as enslaved people resisted bondage and re-established ties among family

and friends. Studies of runaway slave advertisements reveal that more

than half of those running away were thought by their owners to be going

to or hiding among friends and kin from whom they had been separated.

Sadly, although the details of his return are unknown, Prince died in

Deerfield in 1752.

When did slavery end in Massachusetts?

As Abigail Silliman's will reminds us, slavery came to a slow end in Massachusetts and other New England states. Although the 1780 state constitution contended that "All men are born free and equal," it was not until 1783 that a court case successfully argued that these words applied to people of color. The outcome of this particular court case had a gradual effect over the last two decades of the 18th century, but slavery was never legally abolished in the state. In Deerfield, some slaves were not freed until 1787; the legacy of their enslavement persisted for years after.

What did freedom mean?

Gaining freedom did not guarantee freed people all the rights or opportunities

for prosperity that white citizens enjoyed. Hostility, prejudice, poverty,

lack of resources and education made it difficult for freed slaves to

succeed. Lack of economic opportunity forced many African Americans living

in rural New England to relocate to urban areas. However, success stories

do exist. Abijah Prince was granted his freedom by his Northfield, Massachusetts

owner. In 1756, soon after Abijah married Lucy Terry, a slave of Deerfield

resident, Ebenezer Wells, Lucy was granted her freedom as well. Abijah

owned land in Northfield, MA, and Sunderland and Guilford, VT. After the

birth of their sixth child, the Princes settled on their land in Guilford,

VT. Although trouble with white neighbors did occur, the Princes were

able to gain support and protection from the state government.

Credits

This guide was written by members of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association's African American Monument Committee, composed of representatives of museums, schools, and the larger community, in an effort to give greater visibility to African American experiences in Deerfield. Special thanks are due Researcher Mary Hawks, Memorial Hall Museum; Advisors Joanne Pope Melish, University of Kentucky; Kevin Sweeney, Amherst College; and Anthony and Gretchen Gerzina, Dartmouth College; and Committee members Amanda Rivera Lopez, Historic Deerfield, Inc.; Jessica Neuwirth, Old Sturbridge Village; and Suzanne Flynt, Memorial Hall Museum, and other PVMA staff.