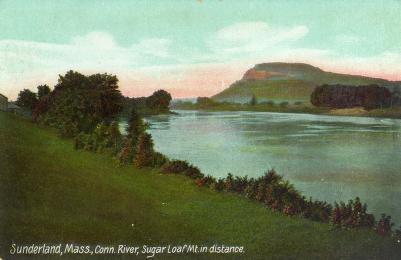

Connecticut River Valley

The Connecticut River is New England's longest river. It flows 410 miles from New Hampshire's northeast corner, along the Vermont-New Hampshire border, and through western Massachusetts and the center of Connecticut before emptying into Long Island Sound near Old Saybrook, Connecticut. The River's name comes from a Native word meaning "long tidal river" (variously spelled Quonehtacut, Quinatucquet, or Quenticut by early English writers who sought to capture its sound). The river formed as the great ice sheet retreated during the last ice age, some 13,000 years ago. It followed a trench formed by a joint in the earth's crust between the White Mountains in New Hampshire and the Green Mountains in Vermont. In Massachusetts, the river joined with the main line of Lake Hitchcock, a glacial lake that extended from central Connecticut into Massachusetts. The glacier's retreat left a landscape of rocks torn from the mountains it passed, while the floor of Lake Hitchcock was made up of sand. The Connecticut River flooded these lands and deposited deep silt layers, particularly in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Generations of flooding formed some of the richest farmland in those states, with loam (rich topsoil) as deep as sixty feet in some places. The first Native peoples of New England found the Connecticut a perfect habitat. The rich lands were ideal for their semisedentary farming, which involved farming fields for as much as a generation before abandoning them to regenerate, much longer than less rich lands would allow. The river itself was a highway, connecting many different Native cultures and enabling trade between them. A series of epidemics resulting from European contact dramatically reduced the Native people's numbers, and they then consolidated their settlements to the best land, the river valley. Europeans became aware of the Connecticut River in 1614 when Dutch sailor Adriaen Block discovered it. The Dutch sought fur-trading links with Natives rather than the extensive landholdings sought by the English, and they hoped to create an alliance with the dominant Pequots. In 1624 they established a short-lived post at the mouth of the river, and in 1633 purchased a permanent settlement near present-day Hartford, Connecticut. That same year, a small group of English settlers purchased land at Windsor, Connecticut. The relationship between the Dutch and Pequots soured in 1635, and the Dutch and English combined with the Pequots' traditional enemy, the Wampanoag, in a war of extermination against the Pequots. With the Pequots destroyed, the English began settling the river (based on a 1620 grant - the Warwick Patent), founding the colony of Connecticut. William Pynchon, an ambitious Puritan businessman, purchased land from the Agawam nation and founded Springfield on the northern edge of the Connecticut grant in 1636. Pynchon sought to enhance the trading links with upstream Native peoples such as the Pocumtucks, and over the next generation he built Springfield into a thriving trade town and made his personal fortune. He became disaffected with the Connecticut Colony, and annexed Springfield to Massachusetts Bay Colony, confirming that colony's western boundaries. After Pynchon's retirement, his son John extended settlements in the Connecticut River Valley northward, founding Northampton, Westfield, Hadley, and other towns. By the 1670s these Puritan settlements extended as far as Northfield, on the present Vermont-Massachusetts border. However, another war with the Native peoples, Metacom's (King Philip's) War (1675-76), forced the temporary abandonment of the northernmost settlements (Northfield and Deerfield), and stunted the northern spread of settlement for a generation. A series of Colonial wars between France and Great Britain limited settlement to south of the Massachusetts-Vermont border. French raiders and the former Native inhabitants of the valley continued to raid the northernmost communities of Massachusetts for several generations after Metacom's War. A period of peace following King George's War in the 1740s allowed for some northern settlement, but it was not until the final British victory in the French and Indian War (1754-1763) that the upper Connecticut River Valley opened for European settlement. Settlers moved continually northward, founding communities all along the valley. In the decades after the American Revolution (1775-1783) the river became the site of some of the country's first industrial activity, as the arsenals at Springfield and Hartford attracted other manufacturers. The river's major impediments to navigation - its falls at South Hadley Falls and Turners Falls in Massachusetts, and at Bellows Falls in Vermont - were circumvented by canals as early as 1791. The building of dams followed. By the mid-19th century, the river's waters were put to a wide variety of industrial uses, including waterpower and the carrying off of wastes. Consequently, the river's other uses, particularly what had been a vibrant fishing industry, badly degraded. By the turn of the 20th century the river was too polluted to sustain large stocks of fish, a situation that continued until the 1960s. Then several factors intervened to begin the river's rehabilitation. During the massive deindustrialization of the United States in the late 1960s and 1970s many factories moved from their old plants along the Connecticut. And the environmental movement began looking at the country's formerly pristine waterways and demanded change. In the 1970s the Clean Water Act began regulating the discharge of pollution, and the Connecticut's water quality steadily improved. Since then the changes have been dramatic. The river has returned to health and its uses have changed with its quality. Formerly an industrial channel, the river has become a prime recreational area. Many Connecticut River Valley towns have changed their economies accordingly. The beauty of the Connecticut River and its valley, celebrated in the first decades of the 1800s and captured by painters such as Thomas Cole (in his famous "Ox-Bow" painting held at the Metropolitan Museum of New York), has come to be appreciated once again.